Introduction

Donald Trump’s term in office as US president ended with an unexpected event—the invasion of the United States Capitol, one of the most important symbols of American democracy, on January 6, 2021, by his supporters. The invasion of the Capitol building in Washington, DC, provided an unprecedented opportunity for challengers of the US global hegemony, including China and Russia, to criticize American claims to exceptionalism and the country’s status as an exemplar of the democratic ideal with an unquestionable right to promote and police democracy and human rights in all parts of the world. The attack on the Capitol also ended Trump’s presidency by further exposing the ugly divisions within American society. It brought to the fore the activities of far-right militias and white supremacist groups amid a drastic anti-immigration policy turn at home and a unilateralist foreign policy that placed American interests before those of others. Operating with the framework of this unilateralist foreign policy, Trump recognized Jerusalem as the new capital of Israel despite protests across the world and facilitated a rapprochement between the State of Israel and other Arab countries.1Julie Kebbi, “Le rapprochement entre Israël et l’Arabie saoudite semble s’accélérer,” L’Orient-Le Jour, November 24, 2020, https://www.lorientlejour.com/article/1242149/le-rapprochement-entre-israel-et-larabie-saoudite-semble-saccelerer.html?fbclid=IwAR0d8xGmnmM7vuUy4GzYaPyCVhtZq_mCJXvshm_uu9yNGDby3qnopZJNAw4 Africa has occupied a rather marginal place in US policy over the past four years—save for in the security sector—although it did not escape a reduction in US financial contributions toward its military commitments in the fight against terrorism. The Trump administration likewise drastically reduced US development aid to the continent.

Trump’s Presidency and Its Impact on the Sahel

The security situation in the Sahel deteriorated considerably after the fall of erstwhile Libyan strongman Gaddafi from power in 2011. This event led to the collapse of the country’s central administration as well as the proliferation of small arms and light weapons, transnational criminal networks, and insurgent extremist groups across the Sahel region. In this precarious context, the humanitarian situation declined sharply due to the combination of collapsed state authority in vast areas, frequent jihadist and terrorist attacks, and the spread of resource conflicts, mainly between pastoralist herders and sedentary farmers. The American presence in the Sahel during Trump’s presidency found expression in its military footprint, structured around a network of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) bases, technical assistance programs to national armies, and the reduction of funds allocated to the training of personnel involved in the fight against terrorism. It also included the provision of reduced amounts of humanitarian and development aid to the continent.

A Constant and Reinforced American Military Presence

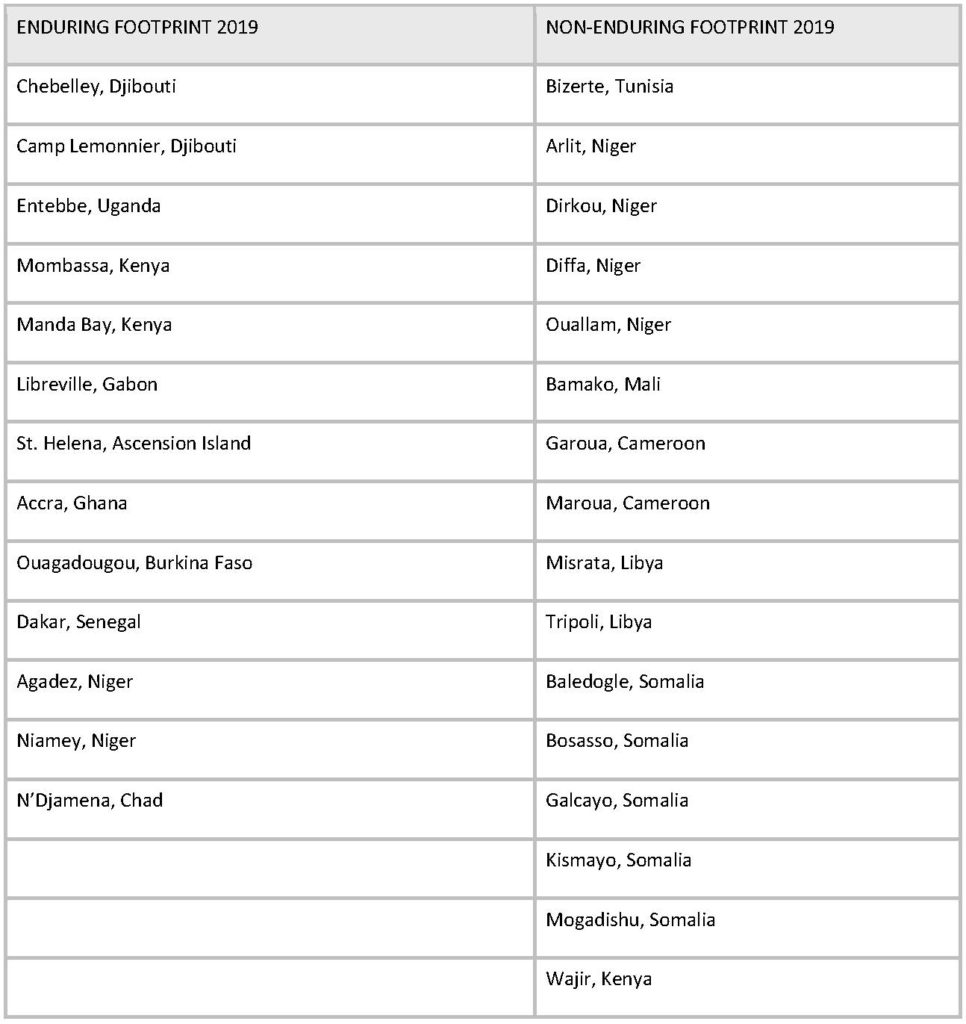

The Trump administration increased the number of UAV (or drone) bases and strikes on the continent.2Nick Turse, “Pentagon’s Own Map of U.S. Bases in Africa Contradicts Its Claim of ‘Light’ Footprint,” The Intercept, February 27, 2020, https://theintercept.com/2020/02/27/africa-us-military-bases-africom/; Abdullahi Halakhe and Anjli Parrin, “The U.S. May Be Readying Drone Strikes in Kenya. That Might Increase the Violence,” The Washington Post, October 1, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/10/01/us-may-be-readying-drone-strikes-kenya-that-might-increase-violence/; Kelsey D. Atherton, “Trump Inherited the Drone War but Ditched Accountability,” Foreign Policy, May 22, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/22/obama-drones-trump-killings-count/; https://issafrica.org/iss-today/drone-strikes-a-growing-threat-to-african-civilians The American strategy was based on special operations and the use of drones for surveillance, intelligence gathering, and airstrikes. The US had thirteen UAV bases in Africa between 2007 and 2016.3Erick Sourna Loumtouang, “War Seen from Above: The Use of Drones on African Soil,” A Contrario 29, no. 2 (2019): 99–118, https://doi.org/10.3917/aco.192.0099. By 2019, this number had doubled to twenty-seven, following an expansion plan that responded to the increase in the number of terrorist groups, as shown in the following table. This significant US footprint on the continent also materialized in an increase in the number of airstrikes during the Trump era. According to Nick Turse of The Intercept, there were more US strikes in Somalia in 2020 than during the entire eight years of the Obama presidency. In 2019, there were sixty-three airstrikes in Somalia, in contrast to the thirty-six attacks from 2009 to 2017 under Obama’s presidency.4Nick Turse, “U.S. Airstrikes Hit All-Time High as Coronavirus Spreads in Somalia,” The Intercept, April 22, 2020, https://theintercept.com/2020/04/22/coronavirus-somalia-airstrikes/. These statistics show that President Trump increased the use of drones during his term of office.

US Africa Command’s “Enduring Footprint” and “Non-Enduring Footprint” in 2019.5Turse, “Pentagon’s Own Map.”

Reduction of Humanitarian Aid

The weakest aspect of the American presence in the Sahel during Trump’s presidency was the reduction in development aid, making American policy exclusively based on hard power to the detriment of soft power. President Trump’s proposed budget to Congress for 2018 included a 28 percent reduction in funding for the State Department and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The administration also suspended the Emergency Refugee and Migration Assistance Fund. Unlike his predecessors, Trump favored the use of other levers of influence. These included economic sanctions, such as exclusion from the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), budget cuts, and the cancellation of military support programs, among others.

What Can We Expect from the Biden Presidency?

The return of US policy to the promotion of American values of democracy, good governance, and multilateral diplomacy under the Biden presidency represents a new opportunity to recalibrate Africa–US relations. This much was made clear by President Biden in his virtual address to African leaders during the 34th Summit of the African Union (AU) in February this year. A major challenge for the Biden administration will be to reposition the United States in terms of its relations with Africa in the face of competitors such as China, Russia, and other emerging powers.

The US needs to consider the issues in the Sahel from a better-informed and holistic perspective, rather than purely in terms of security or strategic calculations. Such a comprehensive approach should consider the complex drivers of the conflicts in this region, including issues related to climate change–induced resource scarcities, food insecurity, fragile institutions, and the absence of state authority in borderlands. US policy in the region should also take into account the high levels of youth unemployment and poverty, the operation of transnational criminal actors that take advantage of porous borders, and democratic regression at the national level. Several studies on violent extremism in the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin have shown that armed groups recruit from among the most economically vulnerable groups in society.

In the context of strategic competition, the United States needs to launch an ambitious program of economic cooperation and empowerment of the continent’s teeming youth population. This policy may take the form of increasing the development aid budget, particularly in the fields of education, IT, and vocational training, and rebuilding social and energy infrastructure. The advent of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCTA) provides an opportunity for the Biden administration to institute an ambitious trade and economic policy on the continent.

President Biden’s actions in the Sahel should be based on mutually beneficial bilateral and multilateral engagements. This means strengthening the capacities of national governments, civil society, and regional organizations to enable them to create more just and inclusive societies, as well as fighting terrorism and broadening Africa–US cultural cooperation. The United States should work closely with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), and the African Union to strengthen and operationalize conflict early warning, prevention, and management systems on the continent. The governments of the Sahelian countries also need to consult with each other and collectively work toward building regional initiatives aimed at harnessing the opportunities presented by the Biden administration’s new Africa policy.