Introduction

The phrase ‘Home to Camp’ is drawn directly from the testimonies of children and youth during research fieldwork conducted across Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps in Northeast Ethiopia. Focusing on their own words illuminates their personal narratives, which include disrupted life courses; stories of lives uprooted by conflict and forced displacement into IDP camps. Grounded in a participatory, arts-based research approach, the interviews with these participants surfaced critical issues that underscore the urgent need for enhanced protection, meaningful participation, targeted intervention, and peacebuilding activities for displaced youth.

An Arts-Based Approach to Hearing Children and Youth

In studies of internally displaced children and youth affected by violent conflict, participatory arts-based approaches play a significant role.1 The application of this method is reflected in theoretical frameworks, like social representation theory2 and symbolic interactionism.3 These frameworks explain how young people employ diverse arts-based approaches, such as drawing, storytelling, and photo-voice. These artistic productions provide valuable research insights and also function as a meaningful intervention pathway.4

An arts-based method was chosen because drawing creates an enabling situation for youth to visually express thoughts and experiences that might be difficult to disclose verbally.5’6 The aim was to explore displaced youth’s life courses in a way that enhances autonomy, rather than conducting a predetermined interview that would restrict them to speaking only on specific issues.7 In contrast, an arts-based method actively engages members of vulnerable groups, enabling them to freely talk about their experiences, life course disruptions, and personal insights, which are all essential for designing effective and trauma-informed interventions. Furthermore, this approach can be considered a form of psychosocial healing, as it provides a structured and expressive outlet for processing conflict-related psychological distress.

During data collection in the IDP camps with conflict-affected children and youth, they shared and disclosed their life courses freely by expressing themselves, and their situation, through art.

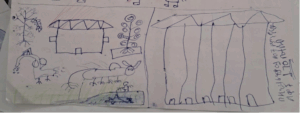

Figure 1: Drawing by a boy, 14.

A 14-year-old boy produced the drawing above to depict his experiences before and after displacement. The first illustrated image is vibrant with fruit trees, a sense of abundance, and a suggested stability. In contrast, the second image is marked by overlapping lines and the enclosed structure of a tent, representing life within an IDP camp.

Voices from the Camps: Testimonies as Evidence

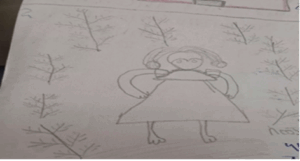

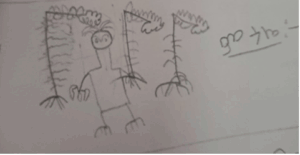

Children and youth in IDP camps in Northeast Ethiopia also reflect on the difficult journey of fleeing their homes, expressing a profound sense of loss for what was left behind due to conflict. Their drawings, as illustrated below, frequently depict people hiding and seeking protection in forests and caves. The following drawings, created by a 15-year-old girl recalling events from five years prior, serve as a visceral testament to the enduring trauma of conflict and the critical need for protective interventions.

Figure 2: Drawing by girl, 15.

In these and other similar illustrations, the research participants stressed the urgent need to end the war and pursue peacebuilding measures to save lives. Thus, such arts-based expressions, alongside interview responses, imply that conflict not only displaces physical bodies, but also severs vital connections: memories, attachments, hopes, and future life courses.

The Policy-Reality Disconnect: Child and Youth Policies, Illusion or Reality?

Despite the ratification of legal frameworks for protecting civilians, the daily reality for children and youth in conflict-affected Ethiopia remains a critically challenging issue. Ethiopia’s adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC), which are inscribed in its Constitution, has, in fact, provided a strong de jure foundation for child rights. Ethiopia also has the National Children’s Policy (2017)8 and the National Social Protection Policy (2015)9, which aim to align with the Sustainable Development Goals and Africa’s Agenda 2063.

However, these extensive policies risk becoming an illusion rather than a reality for children and youth, particularly in conflict-affected zones where young people face compounded victimization and trauma,10 and are forced into daily labor to meet basic needs and support their families. While the formal policy architecture is robust on paper, a critical “implementation dissonance” persists between federal legislative intent and ground-level actions in volatile regions.

Rebuilding Futures: A Youth-Centered Pathway to Peace

As a way forward, interventions must move beyond drafting generic policies and start implementing practical and actionable strategies. This includes providing psychosocial support services, facilitating accelerated learning and alternative education pathways, and developing protection mechanisms designed for youth affected by war. However, peacebuilding policy must be revised beyond approaches that homogenize children, adopting instead an integrated, multi-layered framework that acknowledges and supports the diverse forms of trauma and cyclical violence experienced by children and youth. Ultimately, effective policy must not only list the vulnerabilities and challenges faced by children and youth in crisis, but also emphasize their inherent agency, capacities, and voices as central to sustainable solutions.

Thus, peacebuilding should move beyond the liberal approaches drawing on Galtung’s[xi]framework, which primarily focuses on silencing the guns, empowering people, and strengthening institutions for stability. Instead, it must turn its attention toward grassroots-level findings to help traumatized children and youth before the situation escalates to intergenerational trauma that fuels cycles of violence. A true-turn or shift must be made toward trauma-informed and generationally conscious peace practices.

To make an arts-based approach to peacebuilding effective, child and youth policies should be co-created with young people. To fill the policy gap and disconnect with reality, we need comprehensive, actionable, and context-sensitive strategies to be designed and activated.

Such arts-based participatory approaches offer an effective pathway to support conflict-affected children and youth in Northeastern Ethiopia, protecting their well-being and facilitating recovery from profound trauma. By providing non-verbal outlets for expression, these methods generate critical insights into children’s psychosocial needs. Such insights can directly inform policy by advocating for trauma-informed frameworks,12 training modules for local stakeholders, and the allocation of resources for community intervention programs. To maximize their reach and impact, these approaches must be formally integrated into child and youth protection strategies, ensuring interventions are accessible, sustainable, and culturally grounded.

Endnotes

- Martikainen, Jari, Hadi Farahani, and Sayyed Nader Musavi. “Making Sense of Life in Iran: Afghan Refugee Youths’ Social Representations Through an Arts‐Based Approach.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 35, no. 6 (2025): e70194

- Moscovici, Serge. “Social representations and pragmatic communication.” Social Science Information 33, no. 2 (1994): 163-177.

- Blumer, Herbert. Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and Method. University of California Press, 1986.

- Buser, Michael, Emma Brännlund, Nicola J. Holt, Loraine Leeson, and Julie Mytton. “Creating a difference–a role for the arts in addressing child wellbeing in conflict-affected areas.” Arts & Health 16, no. 1 (2024): 32-47.

- Martikainen, Jari. “Drawing as an arts-based method for researching sensitive topics.” In Handbook of Sensitive Research in the Social Sciences, pp. 132-146. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2025.

- Martikainen, Jari, Hadi Farahani, and Sayyed Nader Musavi. “Making Sense of Life in Iran: Afghan Refugee Youths’ Social Representations Through an Arts‐Based Approach.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 35, no. 6 (2025): e70194

- Literat, Ioana. “A pencil for your thoughts”: Participatory drawing as a visual research method with children and youth.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 12, no. 1 (2013): 84-98. Martikainen, Jari. “Drawing as an arts-based method for researching sensitive topics.” In Handbook of Sensitive Research in the Social Sciences, pp. 132-146. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2025.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs. (2017). National children’s policy. African Child Policy Forum.

- National Social Protection Policy (Addis Ababa: FDRE, 2015), https://molsae.gov.et/

- Demsie, Getnet Tesfaw. “The psychosocial experiences of internally displaced children due to armed conflict in the case of north east Ethiopia: Implications for intervention.” Conflict Resolution Quarterly 42, no. 1 (2024): 165-179.

- Galtung, J. (1985). Twenty-five years of peace research: Ten challenges and some responses. Journal of Peace Research, 22(2), 141-158.

- Buser, Michael, Emma Brännlund, Nicola J. Holt, Loraine Leeson, and Julie Mytton. “Creating a difference–a role for the arts in addressing child wellbeing in conflict-affected areas.” Arts & Health 16, no. 1 (2024): 32-47.