Introduction

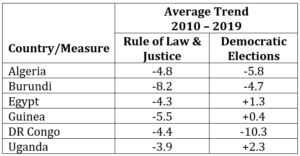

In the last few years, several regions around the world have experienced some form of democratic backsliding, but this trend in Africa has been particularly alarming. As the Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) shows, during the last ten years (2010–2019), significant regression in democratic systems has been recorded across Africa, especially in the areas of rule of law, justice, and democratic elections (see table 1).1IIAG (Ibrahim Index of African Governance). “Governance report 2020.” Accessed June 26, 2022, https://iiag.online/data.

Table 1: Democratic regression in selected countries

Source: Ibrahim Index of African Governance (2022)

This article seeks to address the following pertinent questions: “Why are some African countries experiencing democratic backsliding now? Do African states have weak institutions that are incapable of preventing the emergence of dictatorship, or is the trend the result of the persistence of an undemocratic political culture? Can it be the result of growing socio-economic inequality, leadership deficits, or the unresolved nature of the citizenship question in some countries?” To answer these questions, it is imperative to reflect on the context of democratic backsliding in Africa.

The Third Wave of Democracy in Africa: Understanding the Current Challenges

Within the first decade of liberation from colonial rule, only a handful of African countries practiced a democratic system of governance as many nations slipped from multiparty democracy into military and authoritarian rule backed by the belief that Africa was unique and therefore needed a unique system of governance geared towards national unity and development. However, this changed in the post-Cold War era as many African countries facing popular pressures for change began to return to multiparty democratic rule. Despite the optimism that greeted this democratic wave in the late 1980s and early 1990s, many countries—except Gambia, Senegal, and Botswana, which had established a long tradition of multi-party elections—were caught up in a pseudo-democratic system where elections were conducted mainly to give legitimacy to the regime in power. This led to situations where some leaders held on to power by orchestrating constitutional coups—such as opportunistic constitutional amendments to prolong a president’s mandate and third termism—leading to the emergence and spread of long-term heads of state such as the late Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe (president from 1987-2017), the late Gnassingbe Eyadéma of Togo (president from 1967-2005), Denis Sassou Nguesso of the Republic of Congo (since 1997), Faure Gnassingbé of Togo (since 2005), Yoweri Museveni of Uganda (since 1986), Paul Biya of Cameroon (since 1982), Isaias Afwerki of Eritrea (since 1993), and Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea (since 1979). These authoritarian regimes have engaged in repression of protests, shut down social media platforms, violated human rights, conducted bad governance, and exacerbated economic and social injustice. The situation is further compounded by the manipulation of elections, the absence of the rule of law, and political inequality and violence.

The post-Cold War phase of the transition to democracy in Africa began in the early 1990s and peaked with the Arab Spring, which began in Tunisia in 2011 and eventually spread to Egypt, causing the fall of Hosni Mubarak’s dictatorship.2Jülide Karakoç, “A Comparative Analysis of the Post-Arab Uprisings Period in Egypt, Tunisia and Libya.” In Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Before and After the Arab Uprisings, edited by Jülide Karakoç, 172–99. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2015. This resulted in Egypt having its first democratically elected President—Mohamed Morsi. Although Egypt had a chance to consolidate democracy, it has since slipped back into authoritarianism. The country’s transition to democracy was truncated by the military, when Field Marshall Fattah Abdel el-Sisi overthrew Morsi’s government on July 3, 2013, just one year after Morsi took the oath of office. Constitutional Court President, Adly Mansour, was appointed interim president. Shortly after the coup, the interim government rushed a new constitution through ratification and set the date for elections for a new government. The election took place on May 26–28, 2014, and was won by Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who had led the coup that ousted Morsi’s elected government.3John Mukum Mbaku, “Coups, Constitutional Democracy, and the Rule of Law: Why Africans Must Care.” Cardozo International & Comparative Law Review 4, no. 1 (2020): 35–231. In 2019, a year after el-Sisi was re-elected to another four-year term as president, he had the Egyptian constitution changed to remove the presidential term limits and allow him to seek a third term in office, allowing him to potentially remain in office until 2034.4Merrit Kennedy, “With Constitution Changes, Egypt’s President Could Stay in Power until 2034.” National Public Radio. February 14, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/02/14/694675332/with-constitution-changes-egypts-president-could-stay-in-power-until-2034

Meanwhile, Nigeria, the “largest democracy in Africa,” has not been able to develop a stable democratic system based on the rule of law but has continued to suffer from sectarian violence and significant levels of injustice since transitioning from military rule in 1999.5Leena Koni Hoffmann, & John Wallace, “Democracy in Nigeria.” Chatham House. 29 June 2022, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2022/06/democracy-nigeria In Burkina Faso, the general election of 2020 was held amid growing levels of terrorism, widespread socio-economic tensions, and conflicts between jihadists and government forces. Despite winning the election with a majority, the election was reported to be marred by irregularities of fake ballot voting, while up to 350,000 people in marginalized communities were prevented from voting due to the threat of violence.6France 24 (2020), Burkina Faso’s Kaboré wins re-election, according to full preliminary results. https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20201126-burkina-s-kabor%C3%A9-wins-re-election-according-to-full-preliminary-results Meanwhile, incumbent President Kabore, who won the [re]election, was forced to resign when the military seized power on January 23, 2022. South Africa’s democratic system has also faced several serious challenges, notably, corruption scandals, inequality, and violent protests that sometimes degenerated into xenophobic attacks on African migrants living in townships. Cameroon, which never really transitioned to democratic governance, has been hiding behind the façade of regular elections following the lifting of the two-term presidential limit by a constitutional amendment in April 2008.

Constitutional coups, authoritarian leaders, and the return of military coups as well as violent conflicts and recurring insecurity continue to pose threats to democracy in Africa. The amendment of the constitution to prolong a president’s mandate has been passed in many African countries, including Algeria, Burundi, Cameroon, Comoros, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Gabon, the Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Uganda, and Togo.7John Mukum Mbaku, “Constitutional Coups as a Threat to Democratic Governance in Africa.” International Comparative, Policy & Ethics Law Review 2, no. 1 (2018): 77–182 Mali suffered two coups d’état in nine months—August 18, 2020, and May 24, 2021—while violent extremist groups continue to threaten the peace of the country. The West African Sahel remains one of the most troubled regions as a result of the activities of insurgent militias and violent non-state actors, resource conflicts linked to climate change, and transnational criminal networks. For example, Nigeria is plagued by sectarian violence, including the kidnapping and killing of civilians by the extremist group Boko Haram, militant herders, unknown gunmen, and armed bandits. Meanwhile, Côte d’Ivoire and Tanzania have withdrawn the declarations they made regarding the establishment of an African Court on Human and Peoples Rights, making it impossible for citizens and NGOs to directly access and seek justice in the continental court.

Other factors enabling democratic backsliding in Africa include third termism, digital authoritarianism, and electoral violence. Concerning post-election violence, the ethnic violence after Kenya’s 2007 presidential election nearly destroyed the country’s embryonic democratic system. Thanks to the adoption of a new constitution in 2010, which introduced the separation of powers and an independent judiciary, the country’s rule of law system has improved significantly. Nigeria is yet another country stuck in identity-based electoral crises without significant improvements in the deepening and entrenchment of democracy.8Tope Shola Akinyetun, “The Prevalence of Electoral Violence in the Nigerian Fourth Republic: An Overview.” African Journal of Democracy and Election Research 1, no. 1 (2021): 73–95. https://doi.org/10.31920/2752-602X/2021/v1n1a4. In an unprecedented fashion, the COVID-19 pandemic has aided democratic backsliding in many African countries; especially the ones that had hitherto been subject to authoritarian rule. The pandemic gave African leaders leverage to postpone elections and restrict movements, freedom of expression, and political opposition. For example, elections to various levels of government were postponed in no less than ten African countries, including Chad, Tunisia, Gambia, Somalia, Tanzania, Gambia, Niger, Gabon, Rwanda, and Uganda.9Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, Global overview of COVID-19: Impact on elections, (2022), https://www.idea.int/news-media/multimedia-reports/global-overview-covid-19-impact-elections

Democratic backsliding in Africa is also a result of the prevalence of weak institutions. Democracy no doubt emphasizes citizen participation, the rule of law, and human rights. These are functions of a strong institution capable of making and enforcing laws as well as being able to promote good governance. However, states with weak institutions are unable to control corruption; prevent state capture; prevent or resolve conflict; guarantee citizen participation in governance, human rights, and the rule of law; and ensure public service delivery.10Tope Shola Akinyetun, Weak institutions are the bane of democracy in Africa. Alternate Horizon, 5(1), (2022): 1-5. https://doi.org/10.35293/ah.v10i.4015 There is also the challenge of the lack of transparency and accountability. When left unaddressed, these conditions, therefore, become inimical to democracy and development.

Furthermore, the advancement of digital technologies, which increased civic engagement and activism among youths through movements such as #FreeSenegal, #EndSARS in Nigeria, #Congoisbleeding, #Shutitalldown in Namibia, #Zimbabweanlivesmatter, and #FeesMustFall in South Africa, has also increased government repression. African leaders impede democratic growth by restricting internet freedom and controlling the digital space through internet shutdown, censorship, social media restrictions and bans, internet taxes, and surveillance. The governments of Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Sudan, Chad, Mali, and Cameroon have at various times shut down the internet to undermine freedom of expression and block protests, while the governments of Uganda, Egypt, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe have censored the internet. Also, Nigeria, Sudan, Senegal, and South Africa have invested in surveillance technologies.11Tope Shola Akinyetun, . & V. C. Ebonine, The challenge of democratization in Africa: From digital democracy to digital authoritarianism. In E. Alaverdov, & M. Bari (Ed.), Regulating Human Rights, Social Security, and Socio-Economic Structures in a Global Perspective (pp. 250-269). IGI Global, (2022), https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-4620-1.ch015 It is also important to note that some African states have courted the support of external actors, notably Russia and China, to give them leverage over Western powers, giving impetus to illiberal regimes.

Concluding thoughts

The return of multiparty democracy, which followed the end of the Cold War is once again experiencing a decline. What this portends is yet to be fully seen; it could be a temporary reversal or the onset of authoritarian rule in more countries. The present experience nonetheless is deserving of critical attention from national, regional, and continental stakeholders, policymakers, and leaders. Given this challenging situation, certain measures should be taken to reverse the trend toward democratic backsliding. As a first step, youth civic engagement should be promoted across Africa. As a region with a youth bulge, the role of youths in promoting good governance cannot be underestimated. In addition, youth, women groups, civil society, and independent media must be empowered in Africa. The African Union (AU) and African Regional Economic Communities (RECS) must jointly condemn the circumvention of presidential term limits and put measures in place to sanction erring states. Furthermore, the AU Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance which came into force on February 15, 2012, must be actively promoted in member-states while an updated protocol for strengthening democratic institutions should equally be developed and implemented. Scholars, activists, and civil society should work together to promote democratic and civic education in various states in Africa. It would also be beneficial for peacebuilding programs and institutes in collaboration with youth organizations to develop curricula for promoting the integration of democratic principles and values into peace education, knowledge production, and advocacy training toolkits. Finally, international actors should go beyond the usual condemnation of anti-democratic practices in Africa by supporting the propagation of democratic principles and pro-democracy conditions on the continent.